On July 24, 1959, in the depths of the Cold War, Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev stood face-to-face, close enough to smell each other’s breath. Dozens of journalists and dignitaries crowded around them in increasingly nervous silence as the two argued heatedly. Khrushchev, the bald, brash son of Ukrainian peasants, raised his booming voice and waved his stubby hands in the air. Nixon, nearly a head taller, hovered over him, struggling to maintain his composure but then jabbing a finger into his adversary’s chest. Precipitating this superpower showdown was a disagreement over … washing machines.

On July 24, 1959, in the depths of the Cold War, Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev stood face-to-face, close enough to smell each other’s breath. Dozens of journalists and dignitaries crowded around them in increasingly nervous silence as the two argued heatedly. Khrushchev, the bald, brash son of Ukrainian peasants, raised his booming voice and waved his stubby hands in the air. Nixon, nearly a head taller, hovered over him, struggling to maintain his composure but then jabbing a finger into his adversary’s chest. Precipitating this superpower showdown was a disagreement over … washing machines.

Nixon was in Moscow for the opening of the U.S. National Exhibition, a bit of Cold War cultural exchange cum oneupmanship that followed on the heels of an earlier Soviet exhibition in New York. He and Khrushchev were now in the fair’s star attraction: a six-room, fully furnished ranch house, bisected by a central viewing hallway that allowed visitors to gawk at American middle-class living standards. The Soviet press referred to the house dismissively as the “Taj Mahal,” contending that it was no more representative of how ordinary Americans lived than the Taj Mahal was of home life in India. Actually, it was priced at $14,000, or $100 a month with a 30-year mortgage-as Nixon put it, well within the reach of a typical steelworker.

Pausing before the model kitchen, packed with all the latest domestic gadgetry, Khrushchev blustered, “You Americans think that the Russian people will be astonished to see these things. The fact is that all our new houses have this kind of equipment.” He then proceeded to complain about the wastefulness of American capitalism-in particular, how foolish it was to make so many different models of washing machines when one would do. Nixon countered, “We have many different manufacturers and many different kinds of washing machines so that the housewives have a choice.” From there he expanded to broader themes: “Isn’t it better to be talking about the relative merits of our washing machines than the relative strength of our rockets? Isn’t this the kind of competition you want?”

Whereupon Khrushchev erupted, “Yes, this is the kind of competition we want. But your generals say they are so powerful they can destroy us. We can also show you something so that you will know the Russian spirit.” Nixon took the threat in stride. “We are both strong not only from the standpoint of weapons but from the standpoint of will and spirit,” he shot back. “Neither should use that strength to put the other in a position where he in effect has an ultimatum.”

What came to be known as the “kitchen debate” was a moment of almost surreal Cold War drama. Had it been written as a piece of fiction, the scene could be criticized justly for the belabored obviousness of its symbolism. Here the great historic confrontation between capitalism and communism presented itself in distilled miniature-as a duel of wits between two of the era’s leading political figures. Just as the Cold War combined ideological conflict with great power rivalry, so this odd, unscripted exchange fused both elements, as the disputants jumped from household appliances to nuclear doom without so much as a good throat clearing. Topping it all off, the spontaneous staging of the encounter in a transplanted American kitchen foreshadowed the Cold War’s eventual outcome: communism’s collapse in the face of capitalism’s manifest superiority in delivering the goods. In capitalism, it turned out, lay the fulfillment of communism’s soaring prophecies of mass affluence.

Richard Nixon made precisely this point during his formal remarks later that day at the official opening of the exhibition. He noted with pride that the 44 million American families at that time owned 56 million cars, 50 million television sets, and 143 million radios, and that 31 million of them owned their own homes. “What these statistics demonstrate,” Nixon proclaimed, “is this: that the United States, the world’s largest capitalist country, has from the standpoint of distribution of wealth come closest to the ideal of prosperity for all in a classless society.” However casual his commitment to honesty over the course of his career, on that particular occasion Richard Nixon spoke the truth.

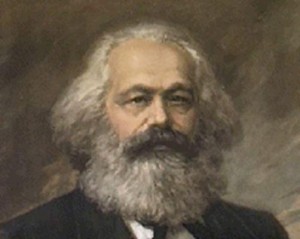

A century earlier, Karl Marx had peered into the womb of history and spied, gestating there, a radical transformation of the human condition. The traditional “idiocy of rural life,” the newfangled misery of urban workers, would be swept away. The normal lot of ordinary people throughout history-to stand at the precipice of starvation-would be exchanged for a share in general abundance. In the new dispensation, the advanced development of productive forces would allow humanity’s physical needs to be met with only modest effort. Consequently, the “realm of necessity” would yield to the “realm of freedom.”

In that brave new realm, according to Marx, “begins that development of human energy which is an end in itself.” A forbidding bit of Teutonic abstraction: what exactly could it mean? Marx was notoriously cryptic about his vision of utopia, but through the darkened glass of his dialectics we glimpse a future in which ordinary people, at long last, could lift their sights from the grim exigencies of survival. Freed from the old yoke of scarcity, they could concentrate instead on the limitless possibilities for personal growth and fulfillment.

It was Marx’s genius to see this coming transformation at a time when the main currents of economic thought led toward altogether drearier forecasts. Thomas Malthus, of course, made his name by arguing-with ample justification in the historical record-that any increase in wages for the poor would be dissipated by a swelling birth rate. Meanwhile, David Ricardo, second only to Adam Smith in the pantheon of classical economists, posited an “iron law of wages” that mandated bare subsistence as the equilibrium toward which labor markets tended. With prophetic insight, Marx grasped that the progress of industrialization would render such fatalism obsolete. . . .